History of the World Roma Congress 1971

- Read Time: 27 mins

THE FIRST WORLD ROMA CONGRESS

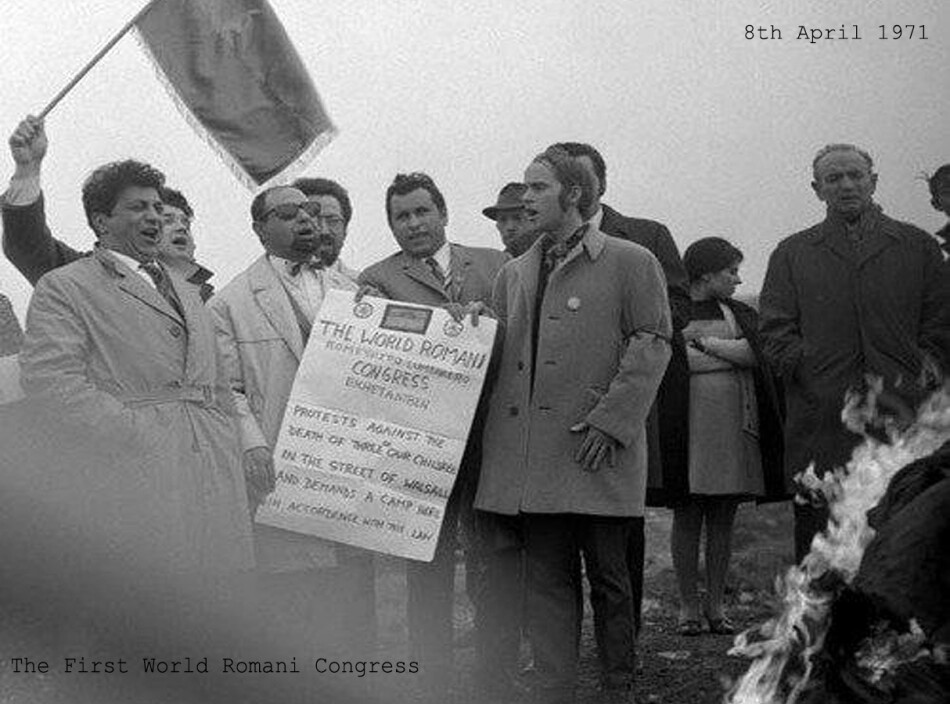

London April 8-12, 1971

By Grattan Puxon

1

Most were unknown to each other before that long April weekend. By the end of it delegates to the 1st World Roma Congress had turned a page in history.

The event that took place at Cannock House, a private school in south London, is now celebrated by Roma communities around the globe. For adherence to a culture, yet there is great diversity; to a common language though many don’t speak it; to a unity which never existed but is gaining reality through the worldwide web.

The political significance of 8 April 1971, the opening day of the Congress, grows exponentially each year.

Decisions were taken that are considered irreversible. They concern status. Delegates declared Roma to be a nation. A nation with ambitions to achieve self-determination. None could say what degree this might reach. But the process was set in train by their call for an end to all those misnomers which signify denigration. Among them cigani, Zigeuner, gipsy. Each a pitch-cap torturing succeeding generations. Disfiguring the image of a people who trace ancestry to Mother India.

Tentative steps had been taken at a 1934 Bucharest congress but the event in London proved to be the one that counted. Forty years later Margareta Matache, a fellow at Harvard, could say that 8 April 1971 was the date when Roma chose the symbols of their nationality; flag, anthem and national day. Ðorđe Jovanovic, director of the European Roma Rights Centre, has written of it as the most historic for all of the estimated twenty millions in the worldwide Roma diaspora. Quote: Nothing could oblige us to mark 8 April more than the moral imperative and hunger for self-definition.

There is a widespread conviction that the London Congress marks a vital moment in the Romani emancipation movement. The blue and green flag, embossed with a red ashok chakra is seen everywhere, adopted by countless NGOs and other bodies. Lately, 8 April has been the occasion for the European Union’s Roma Summits in Brussels, for debate in the British House of Lords, statements by Hilary Clinton, while US Secretary State, and much other official fanfare. This fulsome recognition continues to grow. Yet one notes a subtly downgrading of original intent. Roma Nation Day is now frequently referred to as International Roma Day, or simply Roma Day. I conclude there are those who want to see Roma nation progress stalled by the rising anti-Gypsyism of the new millennium.

2

3

4

Several delegates protested. Žarko Jovanović got to his feet. He had been in on CIT meetings and knew the score. He put his message forcibly, in Serbian and Romani. Žarko proposed Slobodan Berberski for president of the World Congress. Like himself Berberski had fought as a partisan. His influence within the Yugoslav League of Communists would be an asset. The congress, he said, must take place here. The relief was palpable. Though few of us knew this Belgrade intellectual, in the excitement of that morning we took Berberski on tust and elected him without hesitation. Vanko Rouda looked as pleased as anyone.

5

Grief and hatred, prudence, pragmatism and a desire to find a way forward. All these elements vied in the hearts and minds of delegates as they filed out of that first plenary session. Strong emotions had been stirred. Much showed in their faces. Melanie Spitta, a Sinti from West Germany, who with Raya comprised the only female representation, had lost close family members in Auschwitz. Others too were children of survivors. At fifteen, Žarko had experienced a narrow escape from the blockade of his hometown Batajnica, close to Belgrade. In that 1941 action, five hundred Roma had been rounded up and murdered. Mateo Maximoff, writer and evangelist, had been interned in France. More such stories were shared over the coming days and nights. Meanwhile, it was with some relief we moved to the several ground floor classrooms for meetings of the scheduled commissions.

6

7